The ALL Women Team Dynamic: What makes racing in a women's team different.

- dirtyheart

- Apr 24, 2018

- 10 min read

Photo Credit: Andrew McFadden/Cape Epic/SPORTZPICS

If you’ve ever entered a stage race requiring you to compete as a pair, you’ll know that choosing the right riding partner is essential. The partnership will either flourish or fail based on a few elements which need to be considered when choosing a partner. In all partnerships the basics need to be in place.

Clinton Gahwiler provides his expert knowledge on this tricky choice.

“Many factors go into building a successful MTB stage race team, but broadly we might divide them into: fitness and strength, nutrition, technical skills, knowledge and strategy, equipment and the mind. In team-based stage events, there are in fact two minds to consider, and the dynamic between these two presents yet another element to factor into your preparations. Typically we just muddle through this randomly however, hoping that we’ve picked someone who we’ll get on okay with and who will respond okay to the inevitable crises that arise.

But that’s not how you chose your bike. And if you did choose a bike that’s not functioning optimally, you keep working on it. Your partnership should be no different. Ensuring an optimally functioning partnership should be considered just as much a part of routine preparation as ensuring that your bike and fitness levels are up to scratch. After all, it is the mind – and in partnerships also the interaction between the two minds – that determines whether or not everything that you’ve trained at is accessible during the event, when it matters most.

Many problems in mountain-biking partnerships can be prevented by making sure that both parties are on the same page well in advance of the event. Unfortunately we don’t like to rock the boat, and so we often avoid dealing with this crucial aspect until there is a crisis. And then we muddle through that too.

To ensure optimal output from a relationship, you need to be prepared to rock the boat, albeit in a respectful manner, and in advance of the actual event. This is crucial to achieving a solid, stable and trusting partnership for when it is needed most. There are many factors that partners need to get on the same page about, but here are a few key ones. If the two of you agree in advance on the following six points, then I believe the partnership will be off to a great start:

The what: What are your goals? Be clear about what you want to achieve. If you are not both in agreement with this right up front, it can result in subtle differences in attitude and approaches to decisions and circumstances, which ultimately result in very un-subtle and unnecessary conflict.

The how: What are your values? Why are you doing this? How much are you prepared to sacrifice? What kinds of risks are you prepared to take? Each individual needs to think about these things and discuss them openly and honestly upfront. This gives the partnership a chance to either address any significant discrepancies, to accept them, or in fact to choose not to partner up.

Appreciate when your team mate is suffering, tomorrow it might be your turn.

Troubleshoot: This point is not strictly speaking about relationships, but is worth including as all teams should consider it a part of their preparation. People think that preparation is about developing a perfect plan for how you want things to go. In reality, however, perfect preparation is also about planning for what could go wrong. Once you’ve done all the obvious things, then the final stage of preparation is to brainstorm what you haven’t thought about yet – what could go wrong, and how you plan to respond to each of these scenarios. For example, what if one partner is struggling, what if we experience equipment failure, etc. Also, what could go right, and how will you respond to that. I have seen plenty of cases in which people panicked and started doing things differently because things were suddenly going much better than expected.

Plan regular de-briefs: I cannot over-emphasize the importance of feedback. Feedback is gathering information around what is working and what is not working, on the physical, technical, strategic, equipment, interpersonal or emotional levels. Don’t wait for a crisis to discuss the above. Rather schedule brief but regular (eg daily) times during which you pose yourself certain useful questions – absolutely routinely. That way you are more likely to prevent a crisis. Questions should include: What’s working? What isn’t? How am I doing? Any concerns? This debrief structure needs to be clarified and practiced in advance.

Value feedback: This is worthy of elaboration as a point in and of itself. You get two types of feedback – positive and negative. Positive feedback is when you tell me to keep doing something as it’s working. Negative feedback is when you tell me to stop doing something as it’s not working. Both are crucial to your partnership achieving its goals. As soon as you do not give useful information for fear of rocking the boat, you are compromising the partnership’s success. Note that negative feedback is different from criticism. While the former is useful and important, the latter is simply a label given by the receiver of a communication, which seldom serves any useful purpose. If feedback is not useful, just let it go – don’t waste time and energy interpreting anything as a criticism.

Value difference: Any partnership that does not respect difference as an absolutely core value, is doomed to frustration and unnecessary in-fighting. Personality is a classic example. Extroverts get energized by engaging socially on a chit-chat level, but this can become very draining for introverts. They are energized by either having quiet time by themselves, or by engaging more in-depth one-on-one. The latter is on the other hand more likely to be experienced as quite intense and draining by extroverts. Another example is a person’s quirks and routines off the bike, (eg preparing for each day’s riding.) Just remember that the greater the difference in a partnership, the more the potential for conflict. However, if you respect this difference and manage it well, you have more options, a greater source of ideas and ultimately a stronger team.

Humour and perspective: Two important things to keep with you at all time! You have a life outside of this race – regardless of what happens – and as my brother-in-law says; “don’t sweat the small stuff” – cracking a sly joke when things are hurting can be the difference between tears or cheers.

Finally, remember that when you chose a partner in mountain-biking – as in life – you are choosing a total package, with strengths and weaknesses, pros and cons. Too many relationships are unnecessarily destroyed by supposedly choosing a total package, yet not in reality accepting the cons that go with it. In such cases you are fooling yourself, being less than honest with your partner and potentially setting the relationship up to fail. This is not to say that we shouldn’t strive to improve ourselves, but it only really works when the person makes that decision for themselves.”

Photo Credit: Tobias Ginsberg

Why the dynamic changes in women's teams.

To explain how and why the dynamic changes when the team is made up of two women, we need to look at the psychology of how men and women are in a sporting or competitive environment.

So what is psychologically unique about females?

In her book, The Female Brain, psychologist Louann Brizendine explains what makes women’s brains distinctively different to those of their male counterparts. Primarily, her research shows that although smaller than a male’s, the female brain contains the same number of brain cells, only packed together more densely.

There are two main differences between the male and female brain:

1 Brain structure and function

Certain features of the female brain’s architecture are vastly different to those of a male’s white-and-grey matter. These can be differences in shape, size, or allocation of functions to different brain areas.

2 Brain chemistry

As expressed by Brizendine, the female brain is so deeply affected by hormones that their influence can be said to create a woman’s reality. They can shape a woman’s values and desires, and tell her, day to day, what’s important. A woman’s neurological reality is not as constant as a man’s.

Photo credit: www.oakpics.com

But how are these two differences manifested? Here is a summary of how some women’s actions and reactions may differ from a man’s:

• The female brain has a higher level of sensitivity to stress and conflict

• Women use different areas of the brain to solve problems, process language or experience and store strong emotions

• The brain centres for language, hearing, emotion and memory formation are bigger in women

• Men have larger processors in the more ‘primitive’ areas of the brain that register fear and trigger aggression compared to women.

• In the main, women have outstanding verbal agility, an ability to connect deeply in friendship and an almost psychic capacity to read faces and tone of voice.

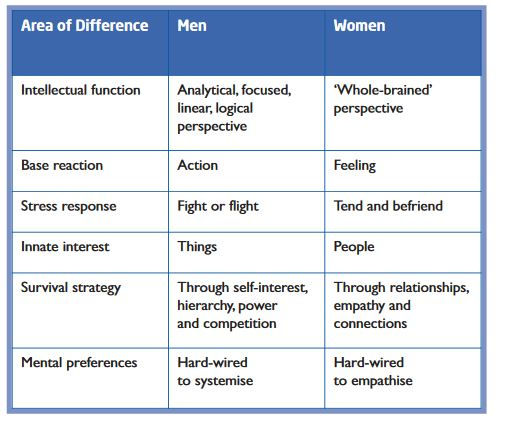

From their study of current literature on the topic, Cunningham and Roberts (2006) describe the following six main areas in which academic research has shown men and women to be different.

Intellectual function

Men show a predisposition to be more analytical, linear and logical in their processing of information, whereas women show a clear tendency to process information in a more ‘whole-brained’ or ‘bigger-picture’ way. This seems to be thanks to women’s brain’s ability to access information from, and make connections with, both sides of the brain in order to solve problems. The use of the ‘whole brain’ seems to explain why women are generally more comfortable with emotion, higher awareness of non-verbal cues and the enhanced ability to look at the full picture.

Base reaction to stimuli

This is not about conscious behaviour, but more about impulsive behaviour. It appears that when things happen, a man’s base reaction is to jump into action, while women are more likely to react emotionally. Science shows that the basal (everyday) state of the male brain is dominated by the ‘fight or flight’ centres

(ie reptilian/instinctive behaviours). In women it seems that more activity occurs in the brain’s limbic system, which deals with emotions and feelings.

Stress response

Hormone concentrations and their strengths vary considerably between men and women. This is even more so under conditions of stress. Studies show how when under stress men produce ‘fight or flight’ hormones like testosterone and adrenaline, while women generally produce more oxytocin which buffers the ‘fight or flight’ response and has a pronounced calming effect. It seems that under stressful conditions, women tend to respond by forming more connections with others and by looking for support from their community. By contrast, men tend to react with alarm, aggression and individualistic behaviour

Innate interest: things vs people

Research into education and the workplace shows that males have a tendency to be more interested in things, while women and girls tend to be naturally interested in people. While men want to understand how things work, women are more interested in connecting and bonding with people, understanding others’ motivations and how they feel.

Survival strategies

Evolutionary theory establishes that, in terms of primary motivations, we exist to ensure the survival of our genes. The key difference seems to be in how men and women go about this. It seems that males strive to survive through self-interest, hierarchy, power gains and competition. On the other hand, women and girls’ survival strategy tends to be through the building of relationships, connections and high levels of empathy. In short, for the boys it is all about being the ‘alpha’ male in the pack, while for the girls, it’s more about getting along with everyone in the group.

Understanding and processing information

Professor Simon Baron-Cohen of Cambridge University shows that in the main, men understand the world by building systems to explain how it works, while women make sense of things by putting themselves into

somebody else’s shoes. For women, it’s not only about being emotionally in tune with another person, but also being able to gauge moods, atmospheres and successfully negotiate interactions with people.

Photo Credit: Tobias Ginsberg

So what does this mean for you?

Generally speaking, this research shows that a woman’s approach to most things is different to that of a man. Drives and motivations, and the way in which these are fulfilled are, for the most part, different for men and women.

For women, and without trying to oversimplify female behaviour choices, this translates into an overall attitude to life based on the following concepts:

• Putting the greater good before their own

• A need to make the environment they work in as safe and appealing as possible

• Added significance to how things and people look

• Thorough decision-making and risk-assessment processes

• A tendency to take responsibility for everything

• Relationships (making and fixing them) matter above everything else

• Collaboration over competition is the main drive within groups.

We can see that the female dynamic centres on emotions and behaviours. For female teams this means a little extra work to curb issues from emotional events which may occur during a race. Females have a need for healthy feedback to move forward and make decisions. If one partner is not willing to take the time to give details and formulate answers, the partnership may fail. It all comes down to perfecting the communication between the two so that each partner feels validated which will ensure success.

We also see that women teams require a certain level of friendship. Women in team sports will often exclude another teammate even if she's a good player while men can still work together on a team even if they don't like certain players. So there needs to be a level of care and genuine interest in the other person for the partnership to work. The more bonded a team is, from an emotional perspective for women, the better they're going to perform.

But women can learn from men, who can be bitter rivals in a race or game and then have a beer or pizza together after with no hard feelings; women often have a harder time letting go. If your partner has offended you or hurt your feelings, women tend to hold onto those emotions and it can affect the team dynamic even days after the event. Both partners need to be aware of this and work harder to overcome these issues.

There is also evidence to suggest that the experience of competition creates more anxiety in women than men, a reflection of the fact that women appear to participate in sport for different reasons than men. Whereas males participate for reasons such as opportunities to be competitive and for a sense of physical achievement, women tend to participate in sport as a means to enhance psychological well-being and to foster emotionally supportive relationships through competition. For amateur women cyclists, competition is a by-product of being involved in the sport rather than an end in itself, which explains why many female cyclists struggle with performance anxiety and reluctance to be “on display”. This anxiety is likely to be greatest among adolescent girls. The more competitive women become, the more they can focus on the competitive nature of the sport, and foster the competitive nature seen in men. It can be harder for women as they will need to override the emotional response with a more practical response as seen in men. This is a challenge we often see in elite women’s racing. It requires women to find ways to work through the emotional response to crisis and then engage in the competitive response in order to succeed.

This acknowledgement that females have a very different psychological relationship with cycling is the starting point for increasing participation and making it more likely that women will stay in the sport. Once you have established that women act and react differently in a partnership, you can begin working on getting your partnership to function smoothly and get the best out of yourself, your partner and the team.

.png)